Western executives are fueling an unusual scramble for high-end housing in Beijing

By JAMES T. AREDDY

December 3, 2005; Page P1

BEIJING -- Westerners have pumped billions into China's economy over the past few years. Now they want a tony address.

The growing presence of executives from abroad in China is fueling an unusual real-estate scramble. In an Asian twist on the pied-à-terre, wealthy and influential foreigners are paying a premium for traditional-style houses here that many Chinese regard as too cramped and too old-fashioned. Known as courtyard houses, they have been razed by the thousands in recent years, and only 3,000 remain in Beijing. Mao Zedong lived in a courtyard and so do many of today's Chinese leaders.

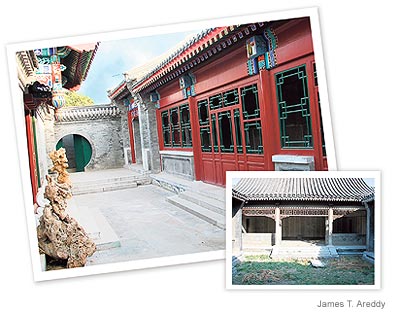

A Piece of History: An American owner restored this traditional Beijing courtyard house.

News Corp.'s Rupert Murdoch and his wife, Wendi, who was born in China, were recently involved in negotiations for one of these houses on one of the most exclusive streets in China, a block east of the Forbidden City's moat, though Mr. Murdoch says he has not made a purchase. Brokers say Jerry Yang, founder of Yahoo Inc., and former Goldman Sachs Group Inc. President John Thornton are both scouting for courtyards. Mr. Yang and Mr. Thornton didn't respond to requests for comment.

The wealthiest buyers are managing to fit swimming pools, satellite dishes and underground parking into the rigid, centuries-old design of the courtyard house. According to blueprints reviewed by The Wall Street Journal, the unfinished home the Murdochs looked at is designed to have a pool in one of two double-level basements, plus a game room with golf and billiards. Unlike traditional courtyards, which are built out of wood so carefully fitted that nails aren't needed, the seven-building compound is concrete. But its layout above ground is traditional, with both an inner and an outer courtyard.

Foreigners are pouring into Chinese megacities like Beijing and Shanghai -- there may be as many as half a million in Shanghai alone. For most Westerners in China, housing now comes down to a choice between a high-rise apartment downtown and an American-style house in a suburban gated community.

For a fortunate few in Beijing, however, the boxy courtyard houses known as siheyuan, or four-sided gardens, have become the ultimate real-estate status symbols. Buying one of these houses, which are miniature versions of Beijing's 14th-century palatial Forbidden City, is an arduous process that can require negotiating with as many as 30 families. Dozens of families were crammed into many of the houses during the Cultural Revolution, and unrelated families may still reside in various rooms of the same house or in makeshift shelters erected in the open courtyard. They are all entitled to compensation for moving out. That can make striking a deal to buy out the residents even harder than finding a property.

But would-be owners see the courtyard house as the epitome of Chinese domestic life, a link to 5,000 years of history that's worth the $1 million or more that French architect Pascale Desvaux says is the minimum price.

Ms. Desvaux and her husband Georges Desvaux, the head of consultancy McKinsey & Co. in China, live with their children in a simple courtyard. It is tucked into temple grounds that were set aside for the family of a Chinese emperor a century ago and later for Tibet's spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama.

That history makes Ms. Desvaux reluctant to tinker. Still, she changed the size of some doors and installed a passageway to link her daughters' bedroom to the main house. "This is a total fantasy, not a Chinese way of doing things," she says.

Historically, courtyard houses were located within Beijing's distinctive maze of narrow urban footpaths called hutongs. The courtyards' outer walls are built right along the street, so widening the hutongs means knocking down the houses. Fewer than 50 of these lanes are now protected from development.

14th-Century Style: A new courtyard house, left, with traditional woodwork and painting. An unfinished pied-a-terre, below.

But the Beijing Municipal Government has strict guidelines that make restoration of courtyard houses an expensive proposition. You can't uproot trees, for example, and the size of windows is dictated. So is the kind of paint for the outer walls. And because many of the houses sit in neighborhoods that aren't hooked up to city sewer systems, running pipes for heating and toilets adds to the costs. Nevertheless, most Western buyers have managed to do extensive renovations, adding up-to-date plumbing and triple-paned windows.

When Pulitzer Prize-winning American photographer H.S. Liu first set eyes on a traditional Beijing courtyard house that was up for sale, it took him a mere 30 seconds to decide to buy it. Then he gutted it. "A lot of those rooms were totally worthless," he says. "I had to push it down." He followed convention by painting the outside walls with the requisite pig's blood, but he also put in a sauna and skylights over a stainless-steel kitchen.

"The scariest part was when they built the basement," says Mr. Liu. He worried that the digging might hit one of the tunnels that Chinese leaders are rumored to use to whisk around town. Now he has a movie-screening room. Mr. Liu left untouched the courtyard's 100-year-old pomegranate trees; at garden parties each fall, he mixes their rosy fruit into martinis.

American lawyer Laurence Brahm has lived in China since the 1980s and owns three courtyards, one of them a hotel. He boasts that "aside from the piping, the electricity and the heating, everything else is original." Except, of course, for the bar he put into an underground bomb shelter that was probably once a septic tank.

He says guests at the Red Capital Residence hotel in one of his courtyards -- the "East Concubine Suite" goes for $190 a night -- often ask him for help in wading through bureaucracy so they can buy their own siheyuan. "I just say, 'No. Good luck,' " Mr. Brahm says.

A classic courtyard embodies principles of feng shui. You enter through a red gate that opens onto a solid wall meant to block bad spirits. A zigzag brings a visitor to buildings arranged in a U-shape around the outer courtyard. Blood-red pillars and gray bricks support squat tiled roofs edged with a latticework in bright green, blue and gold, with figures of flowers and birds.

To go from one room to another, you must step out onto the uncovered courtyard, a chilly proposition during the brutal north China winter. But it's also part of the appeal. Says Hong Kong architect Kamwah Chan: "Your feet are on the ground and you look up to the heavens."

--Kersten Zhang contributed to this article.

Write to James T. Areddy at james.areddy@wsj.com